Redis Locks and Fencing Tokens

Redis Locks and Fencing Tokens

Lot of times out of the box Redis locks are used for ensuring mutual exclusion between workers. However, the redis based locking mechanism actually needs some additional handling to avoid any unexpected behaviours.

Locks with redis can be implemented with two ways1

- Single master - just use a single key acting as a lock with TTL. If the key already exists, the operation fails, indicating the lock is held by another client.

- Multi master - Redis provides distributed lock with Redlock implementation

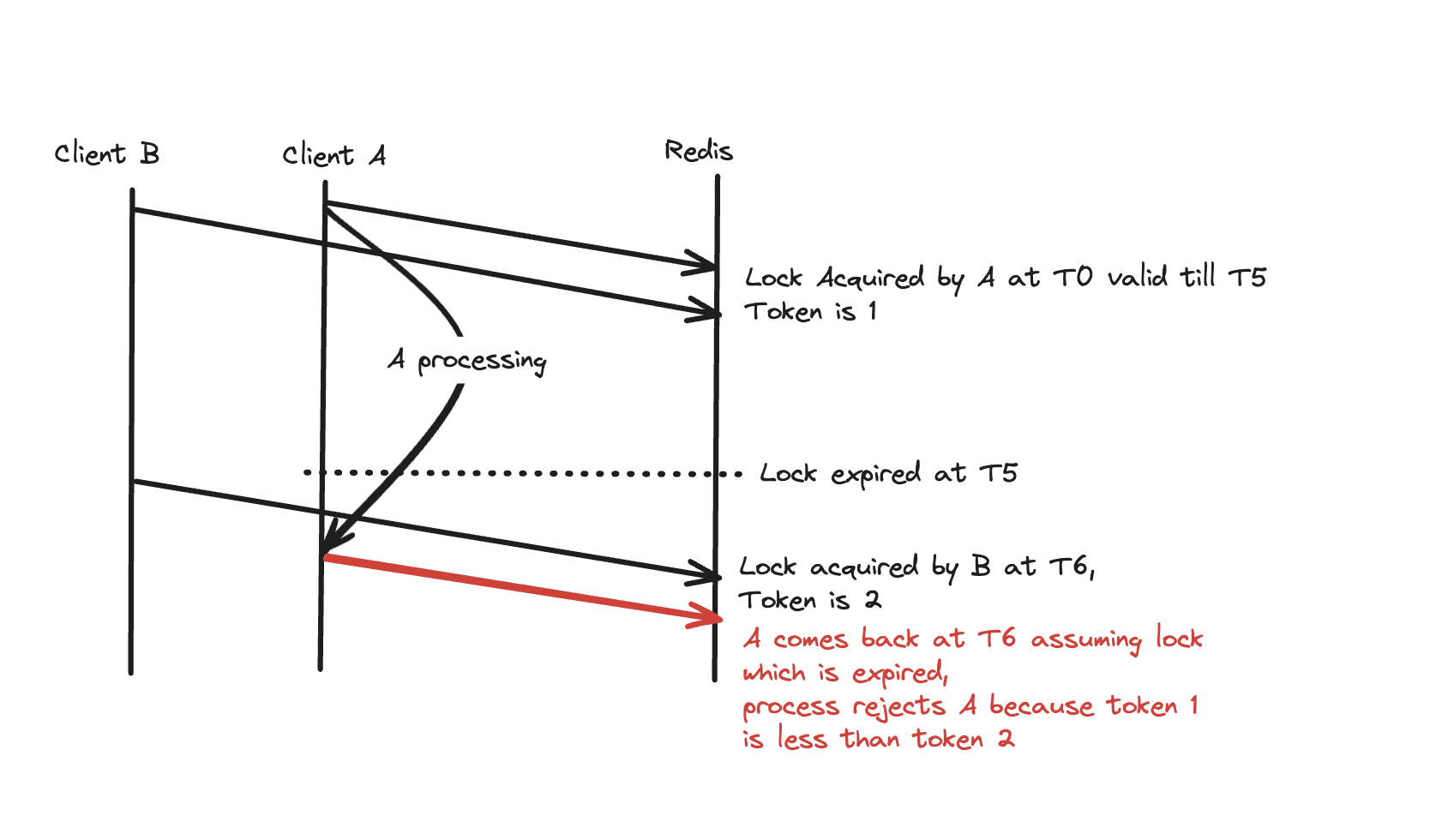

The Problem: Unexpected Client Delays

While this basic implementation seems sound, it has a critical vulnerability. Consider this scenario:

- Client A acquires the lock

- Client A gets paused (GC pause, network delay, etc.) for longer than the lock timeout

- The lock expires and Client B acquires it

- Client A resumes and continues its work, unaware it no longer holds the lock

- Both Client A and Client B now operate on the protected resource simultaneously

This scenario violates the fundamental purpose of a lock—ensuring exclusive access.

Imagine this was seat booking system, Client A took long time for payment and came back meanwhile lock expired and B booked same seat - basically two people booked same seat - very bad.

That means this locking mechanism can end up causing inconsistent state violating mutual exclusion. While this is not the fault of the lock itself, but rather the way the system is using the lock.

Enter Fencing Tokens

Fencing tokens solve this problem by adding a monotonically increasing number to each lock acquisition:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

def acquire_lock_with_token(lock_name, timeout_seconds):

# Get the next token value

token = redis_client.incr(f"lock_token:{lock_name}")

# Try to acquire the lock with this token

if redis_client.set(f"lock:{lock_name}", token, nx=True, ex=timeout_seconds):

return token

else:

return None

def release_lock(lock_name, token):

# Only release if we still hold the lock with our token

current = redis_client.get(f"lock:{lock_name}")

if current and int(current) == token:

redis_client.delete(f"lock:{lock_name}")

With this approach, the client receives a unique token when acquiring a lock. When interacting with the protected resource, the client must present this token. The resource manager (or the storage system itself) can verify that the token is the latest one issued, preventing “zombie” processes from causing harm.

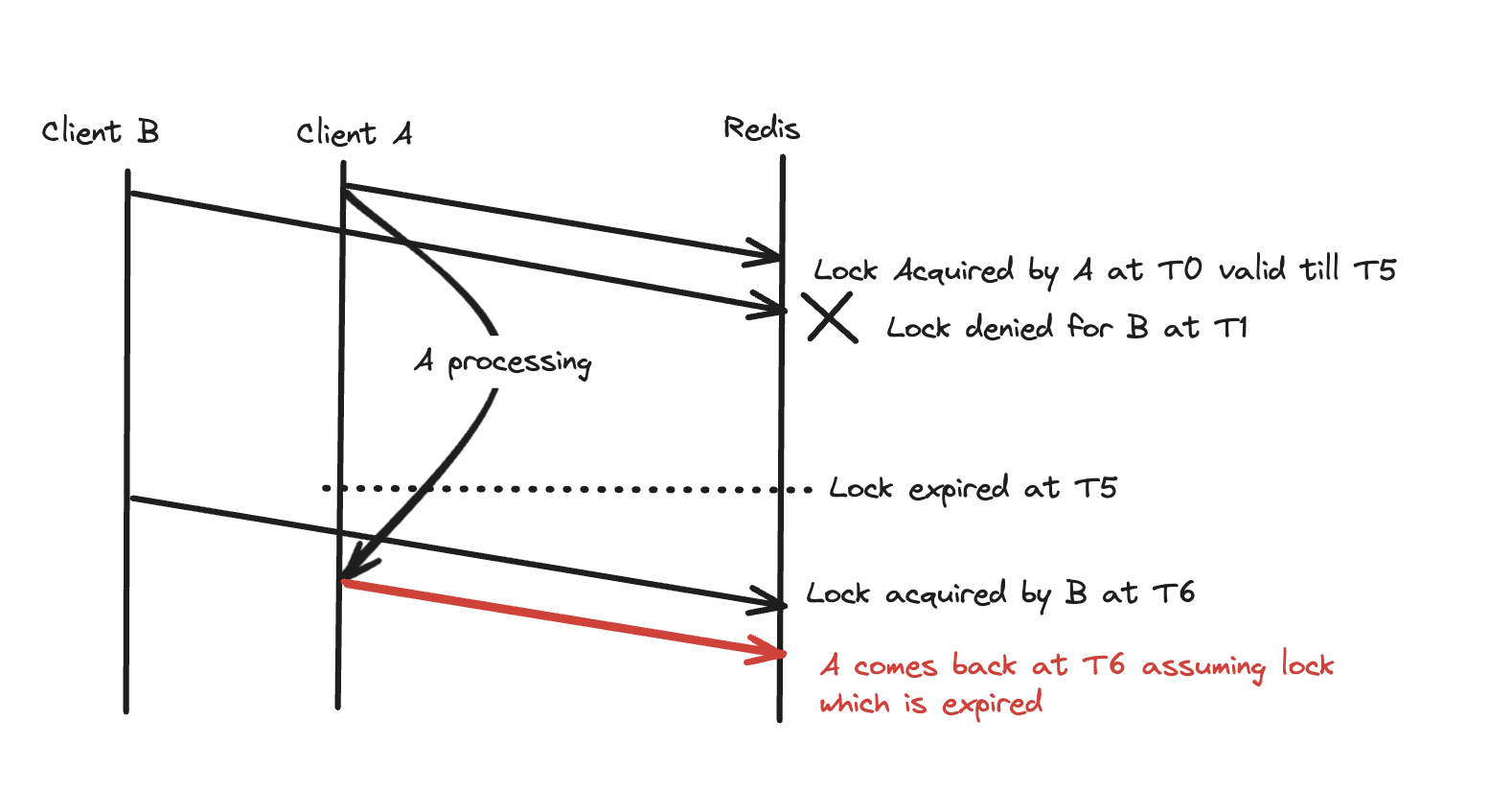

How Fencing Tokens Prevent Data Corruption

Let’s revisit our problematic scenario with fencing tokens in place:

- Client A acquires the lock and receives token 1

- Client A gets paused for longer than the lock timeout

- The lock expires

- Client B acquires the lock and receives token 2

- Client B makes changes to the protected resource, tagging its operations with token 2

- Client A resumes and attempts to access the resource with token 1

- The resource manager sees token 1 < token 2 and rejects Client A’s operation

This mechanism ensures that even if a client experiences a long pause and continues operating after its lock has expired, it cannot corrupt data because its token is now considered stale.

Lets consider the same seat booking system - when Client A comes back, its request will be rejected as the token has moved forward and it wont actually book the seat for A.

However this means that the system now also needs to handle scenarios where clients are rejected - here it may be that user already has paid, so we need to handle the reverse ie issue refund etc.

This also means that the service also need to verify the tokens too - this is additional overhead on the service with fencing token.

Conclusion

Based on the actual domain problem being solved, the out of the box lock with Redis won’t be a foolproof solution and it needs additional safeguarding.

Fencing tokens help here by ensuring that delayed or “zombie” processes cannot corrupt shared resources.